Monday, January 30, 2012

Finding Flow

Saturday, January 28, 2012

Purity

Friday, January 27, 2012

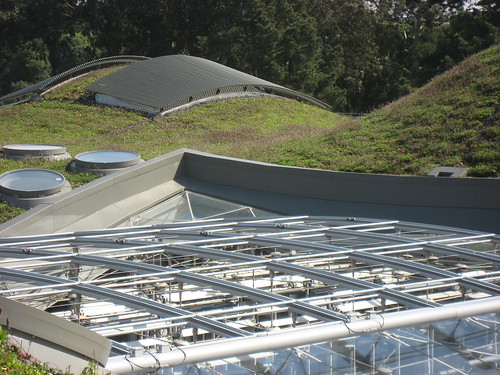

Sculpting the Land, Scarring the Land

Thursday, January 26, 2012

Metacognition

For the past few years I've asked my non-major students to "model" scientific concepts by creating short videos that they post on YouTube. The results are varied. Some students seem to "get it," and their videos reflect time, energy, and thought that they put into the project. Most students seem to make videos that don't reflect much time or energy and the results are disappointing.

I've changed my outlook a bit and I still have students do videos, at least during one semester, but my work in the clay studio has taught me a thing or two.

Students in ceramics are taught to do pinch pots, coils, and slabs. All of these recall the human origins of working with clay. They are the bedrock of traditional ceramic practice and they are thousands upon thousands of years old. Since ceramic work must have started as a way to make vessels, these traditional methods are perforce ways of making pots. Glazing is another technique that is essential to making useful vessels. But are any of these methods necessary to building ceramic sculpture?

I'll get back to that question in a second but it brings me to another, connected thought. Why must science learning involve the orthodoxies that people in high school and college struggle with in order to master biology, chemistry, and physics? Aren't there ways that we can educate people about science without putting them through the paces of classic science practice? Not that these aren't useful, and they certainly are historically important, but are they necessary for a grasp of the processes of nature?

Back to clay. The student results of coiling, slabbing, etc. are very often cutesy cirliqued confections, hearts, squids, flower petals. Then they get glazed and they look like an 8th grader did them. I know students put "time" into them because I see them at work. But the results are something like the unsatisfactory videos many of my students make.

Why don't we train students in a ceramic sculpture class to look long, hard, and deeply at nature before we even have them touch the clay? Similarly, why can't science training be based first and foremost on observation of the natural world? And I don't mean laboratory.

Why this screed on science and art learning? It seems to me we need to encourage a different kind of learning for non-majors. This applies to students like mine who are in their last required science course for the rest of their life. I think it applies as well to students who are in their final semester of college-now finished with their requirements and finally taking an art elective that happens to be ceramics.

We need to let students engage our disciplines at a level by which they can observe their world, take it apart through their own eyes, connect nature with practice, and create work that's both original and mindful. It doesn't matter whether these students can balance an equation or throw a pot because these students may never be scientists or ceramicists. But by leading them through a process of self-conscious observation and practice, albeit informal, we will let them discover their own voice, perhaps leading them to understand why they do what they do. Metacognition.

Wednesday, January 25, 2012

Centering

I asked Janet the same question today. She doesn't make art but she prepares wonderful dishes with grace and simplicity. They are works of art.

So it got me to wondering, if it isn't art, can it still be "art?" In other words, if we look at art as a centering activity, one that commands focus, attention, and calm while providing relaxation and the opportunity to "get out of oneself," can we recognize some kind of relationship between "art" and "non-art"?

I actually had a similar conversation with Lucy the other day when we talked about focusing on a math problem, or a young child focusing on a play activity. The kind of intense, intimate channeling of energy, call it "centering," that is nevertheless totally outside of oneself...is this a similar cognitive space to the one in which art is created?

Maybe there's a way to further break down the question. For one thing, leave the product out of it and focus on the process. So the process of intense focus that makes art or inspires you to polish your car...what is it?

Tuesday, January 24, 2012

Art in Hidden Places

In this picture in I took in the moist uplands of Chiapas State in Mexico numerous species of orchid, spanish moss, and other species, are hanging from a tree branch. Who knows what smaller species, probably microscopic, live in the hanging bundles of epiphytes?

What does this have to do with art?

Before on these pages I've discussed how art is an extension of the human brain and body, a kind of biological extension of the artist. Maybe it's because I've spent so much time in recent months squeezing clay, but it seems to me that art is something that gets squeezed out of the artist, something that lives in and with the artist, something that moves from the hidden recesses of the artist out into the open. Part of the strangeness of art I think is that it comes from such a private place. And at the same time, once the work is finished it is "out there" as an expression of that hidden place it emerged from.

Imagine if all the small critters hidden in the plant bundles on the branch marched out and lined themselves up under a microscope. We would learn something about the habitat, the life cycle, and the evolutionary history of each one. My thought for today: Maybe the work of art reflects a similar set of realities about its maker.

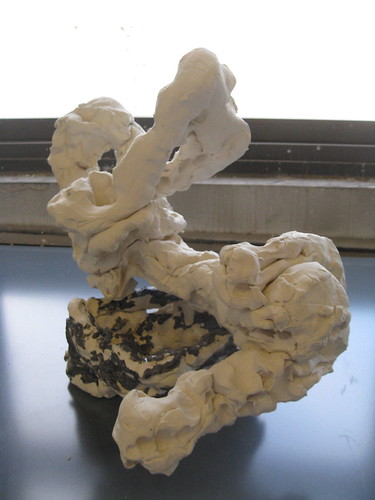

I made this sculpture in the fall. I call it "Olmec Baby's Dog." It's very thick hand-squeezed clay with a pigment and wax finish.

Monday, January 23, 2012

Details, details...

A couple more photos of details on the Heart's Portal sculpture. One of my challenges has been how to balance these large pieces of clay to make them both free-standing and reflective of their increasing size. I started to make bases for them, similar to this one.

Here's the point of attachment at the base of last fall's "Phospholipid" sculpture. I think the moment between base and the main sculpture is surprisingly provocative and exciting.

The base plays a dual role of support and highlighting the main sculpture. What do you think? I also wanted to show you a detail of the surface on the base from "Portal." I fired on some of my own recipe...a black clay slip with sand, bicarbonate of soda, and some cobalt blue glaze. When I painted near it with very light blue oil paint (thinned) I got a nice interplay between the rough stuff and the very smooth paint. Another point of provocation and challenge. Lots of movement too, and it looks geographical, which surprises and delights me.

Today I applied for a fellowship at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, MA. A wonderful community and a superb opportunity if I'm lucky enough to be admitted. Maybe it's just another snowball's chance but I became incredibly excited sending in the application. Like I recognize something in myself. As an emerging artist I think I have a lot to offer, a body of work that shows an increasingly cohesive voice, and a strange, vibrant energy that translates into my work. Not to toot my own horn but it's an exciting way to launch into sabbatical year.

Saturday, January 21, 2012

Heart's Portal to Nature

I call it Heart's Portal to Nature not because it's shaped roughly like a heart. Instead, I want my outdoor sculpture to draw one's vision and heart to nature.

Friday, January 20, 2012

The Power of Fire

Friction, pressure, and heat play such an important part in the formation of our physical world, and not just the terrestrial environment. One truly amazing experience is to see meteors close up. They are the product of extreme heat, which condenses, purifies, and molds the physical world.

Thursday, January 19, 2012

Ephemeral Sculpture

Wednesday, January 18, 2012

Back to the Studio

Thursday, January 12, 2012

Erosion and Flow

How cool would it be to make unfired ceramic sculptures and watch them disintegrate due to erosion? The natural process of erosion in nature provides so many beautiful shapes, full of randomness yet highly patterned.

Hopefully this year I’ll have a chance to do some unfired outdoor sculpture and document the effects of weather on the green clay. I have a feeling I’ll be in for a few surprises because in nature, clay is more resistant to the elements than other soils.

Wednesday, January 11, 2012

Art in Conversation with Nature: A Moment or Millenia?

I like to think about how sculpture reflects natural process. It’s one thing to think about form, which the static sculpture presents at first look. It’s something else to think about the processes that make the form happen in the first place.

When we look at art, just like when we look at nature, we are seeing a “snapshot” of a moment in time and space. We can take it at face value or we can look deeper at the object (or the ecosystem) to try to discern its evolutionary history.

In the case of an artwork it may have been created over some hours, weeks, or years. When we look at natural form we are looking at anything from a moment to hundreds of millions of years.

Tuesday, January 10, 2012

Art and Environmental Remediation

I was thinking about how art might play a role in remediating developed landscapes. This is different from wholly natural landscapes, where art might highlight or complement the shape of nature but not take its place.

Consider the beauty of a “specimen tree” or any tree in an ecosystem, and its role in the landscape. The sculptural element of the tree speaks for itself.

But what about in the built environment? Can art “remediate” the developed landscape? It’s a question we can look at from several perspectives.

When I was a teenager living in Chicago we got a trio of monumental pieces of art in the center of town: the Picasso Statue at the Cook County Building, the Chagall Mosaic at what was then LaSalle Bank, and, west of downtown, the Claes Oldenberg Baseball Bat. All three of these pieces did do something to highlight the landscape. As focal points they ameliorated an otherwise rough urban environment. But as works of major artists they stood on their own too. They had little to do with the places they were installed, and nothing in common with the non-human natural environment of the city. Had they been placed in parks it might have been a different story but would they have achieved the "glory" (I add this tongue in cheek) that they demanded as works of major artists?

Fast forward to the upper Midwest. A few years ago I was at a conference in Madison, Wisconsin. The center of town was dotted with what I considered to be pretty awful cow sculptures, decorated, bejeweled, painted, lighthearted, silly. They highlighted the social landscape of Madison as the capital of the cheese state. But did they remediate?

Consider the famous Smithson Jetty in the Great Salt Lake. Another masterpiece. Another art star. A statement. Connected with nature or plopped down in nature? A remediation?

So, thinking about art and how it can remediate the developed environment, I’d like to propose an alternative. Perhaps art can provide a portal through which viewers can come to understand their place in the world more thoroughly. At the same time, maybe they can come to understand nature in a more complete way.

I guess I’m arguing for less “star” art (the Chicago trio or the Jetty) and less “cute” art (the Madison cows). What about art that frames the landscape, providing people with a focal point that allows them to think “I stand here” visually and phenomenologically?

I’d like to argue that such art need not be monumental. Perhaps even small pieces can act as focal points.

Larger pieces, perhaps installed in patterns, could also provide a sense of place.

Lots of potential points of discussion here. I’d love to hear what you have to say.

Sunday, January 8, 2012

Color

I am addicted to color. As a scientist I use color to understand so much about the natural world. In my teaching I try to incorporate color to bring a feeling of comfort, inclusion, and interest to my students who otherwise might not feel so engaged in science. We see color in nature in so many contexts:

When I started in working on ceramics I wanted to make things in vibrant color. But the glazes at our studio were muted and “natural,” beautiful in their own right and sometimes exciting, but not vibrant. At Medalta this summer I saw one of the artists-in-residence, Koi Neng Liew, using regular latex paint on his work. This led me down a whole new path. I experimented with color a lot this past semester.